Different Games Name With Pictures

One of the best books ever written about the rich, John P. Marquand's The Late George Apley, is not really about money, power, or the things we associate with wealth. It's about time. George Apley, the graying scion of a patrician Boston family, is looking around at the end of his life and is troubled by what he sees—namely, too much money in the hands of the wrong people (not his). Yet he's confident that in the end the battle for time—the future—will be won by his sort, citizens "of high thought and plain living." The Apleys' defining characteristic, in George's eyes, is not their considerable wealth but their values, embodied by the family Rembrandts hanging in the Museum of Fine Arts, the perennial spot on the Harvard board, and, perhaps above all, a commitment to philanthropy, all done with the Apley "dislike for external show."

Philanthropy has always been a favorite tool of the wealthy, whether to advance a cherished cause, change public perception, or ease a guilty conscience. Because it's so public—is any staple of the front page more enduring than news of the latest megagift?—it inevitably invites armchair psychologizing, none of which is ever very flattering. After Andrew Carnegie started endowing public libraries in the 19th century (a staggering 3,500 would eventually be built, largely in parts of the world where need was judged to be highest), Mark Twain called the project a shrewd plan not to elevate mankind but to secure the Pittsburgh titan's immortality. "He has bought fame and paid cash for it," the author wrote. "He has arranged that his name shall be famous in the mouths of men for centuries to come."

Ego is of course a character trait associated with money. However, not even somebody like Carnegie could prevent a richer man than he from coming along.

Paul Smith's College, in upstate New York, isn't the sort of school that comes into frequent contact with great wealth. Located in a county within the Adirondack Park where per capita income hovers around $21,500, it tends to educate local youths and, because it's a trade school with offerings concentrated in hospitality and land management, send them into adulthood with skills for earning a living, not ruling the world. The members of its small alumni body (the school graduates only about 250 students a year) are unlikely to have extra millions on hand for the next capital campaign. More than 85 percent of the gifts the school gets come from a group of 100 or so benefactors—virtually none of whom, by the way, is an alumnus.

To make matters considerably more challenging, Paul Smith's gets by without the support of state funds (unlike any number of technical colleges), on a relatively small $27 million endowment. Do the math (in 2013 the operating budget was $36.6 million), and it's not surprising that the school lately has been in something of an existential struggle.

But not long ago a generous variable with grand ambitions came into the equation: the Weills, Joan and Sanford, a billionaire couple with a lifetime of philanthropy to their names. Sandy Weill, as he is known, was formerly CEO of Citigroup, and over the last few decades he has given so many hundreds of millions to so many causes, especially in New York City, that the Weill name has become virtually ineluctable. There's Weill Cornell Medical College on the Upper East Side, Weill Recital Hall at Carnegie Hall, the Joan Weill Center for Dance at the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, and so on. Joan Weill took a liking to Paul Smith's some 20 years ago, after she and her husband, who are both in their eighties, bought a country house in the area. Though nobody in their family has studied there, in 2002 they set about donating more than $10 million to help the college build a new library and student center—both of which were named for her—and raised nearly $30 million more from other donors.

In 2015 the Weills pledged their largest gift yet, $20 million, to be spent at the discretion of the administration and trustees, on whose board Joan sits—with a major condition attached: The entire college had to be renamed Joan Weill–Paul Smith's College. As it turned out, the college's founder (the son of Paul Smith, a hotelier of some renown) had stated in his will that the school he was endowing was to be "forever known" as Paul Smith's College of Arts and Sciences. Forever would seem to be a word without vagueness, but you know lawyers: A case can be made for anything, and once the president and trustees declared that the charter's definition of forever must be flexible just so that the institution could endure, many hurdles were cleared. The matter went before a judge, however, who was unsympathetic. The school's effort to redefine (or simply ignore) forever fell short, he wrote, "of showing that its name is holding the College back from being a shining success both in enrollment and in producing successful college graduates."

And with that bit of bad news, the Weills rescinded their gift. The opprobrium that followed was swift. In Nonprofit Quarterly, the social justice scholar Pablo Eisenberg opined that Joan Weill had "inscribed herself in stone as one of the greatest, most insensitive egos in today's philanthropic world." ("She didn't even have the humility to demand the name be changed to Paul Smith–Joan Weill's College," he added.) One online commenter suggested the Weills deserved a prize "for the grossest pseudo-philanthropic act of the year."

By this logic the only true philanthropy is anonymous, the kind that "sounds no trumpet," as Jesus says in the Sermon on the Mount. Judaism commends undercover giving as one of the highest forms of charity (behind only charity that eliminates the recipient's dependence on others), and the Koran, while allowing that "if you declare your charities, they are still good," recommends that you keep them anonymous. "God is fully cognizant of everything you do."

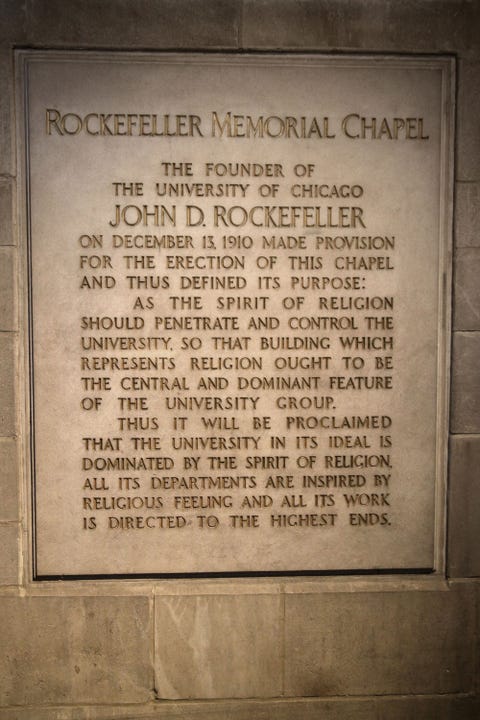

Practical reasons for not sounding the trumpet abound as well. In the 19th century John D. Rockefeller gave $80 million to found the University of Chicago and insisted his name appear nowhere on campus (although it now adorns the school chapel). Modesty? Shyness? Maybe Rockefeller just didn't want the world to know how generous he could be; his assistant once told a reporter that more than 500 solicitations a day arrived in the mail, requesting gifts ranging from $5 to $1 million. (According to Titan, Ron Chernow's biography of the co-founder of Standard Oil, Rockefeller also believed that plastering your name on a university, as fellow tycoons Carnegie and Leland Stanford had, fostered dependency.)

More recently, in 2014, Gert Boyle, the chair of Columbia Sportswear, was revealed as the secret patron behind a $100 million bequest to the Oregon Health & Science University, which seemed odd, since Boyle had given significant gifts before—publicly. The unfortunate explanation: Not long before making her megagift, Boyle had been attacked inside her home by robbers, and afterward she decided to lower her profile.

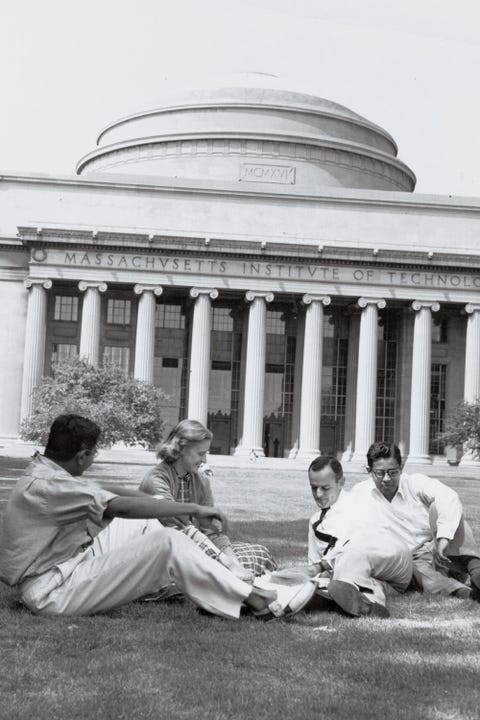

It's often assumed that anonymous giving is one of those bygone values, like a taste for simple things, unsuited to the affluent of today. (Sure enough, George Apley prides himself on his family "anonymously contributing three million dollars to the South Boston playgrounds.") But anonymous giving hasn't been popular for a long time. In 1912, according to an article in the New York Times, during a banner year for charity in the United States—nearly $250 million was given away, more than in any previous year—less than $4 million was donated anonymously. Moreover, nearly all the unnamed donations were directed to colleges and universities, such as MIT, where George Eastman, founder of Kodak and an intensely private man known to micromanage his philanthropic works, underwrote an entire new campus under the name Mr. Smith. (Only MIT's president, his secretary, and his wife knew his identity.)

Nowadays fewer than 1 percent of charitable gifts by the affluent are anonymous, according to Indiana University's Center on Philanthropy (which conducted its study 25 years ago, the last time anyone gauged this difficult-to-appraise phenomenon). Among the living, America's most famous (formerly) anonymous donor is Charles F. Feeney, a duty-free shopping magnate who in 1997 revealed that he had sold his $7.5 billion empire and was furiously giving away the proceeds. (Feeney's desire for secrecy was such that he set up the foundations responsible for disbursing his fortune in Bermuda.) Over the years, profiles of Feeney have been written extolling with a $2.5 million donation his unfashionable humility ("The Billionaire Who Is Trying to Go Broke"), but in terms of name recognition, he has pretty much gotten what he wanted. He's no Bill Gates.

And the truth is, being Bill Gates helps. "Anonymous donors are not ideal," says Scott Nichols, head of development at Boston University and former dean of development at Harvard Law School. "Philanthropy is a happy virus, and it spreads better if the donors are known." Nichols cites the $105 million donation that Robert W. Woodruff, president of Coca-Cola, gave to Emory University in 1979: "He gave so much money I'm surprised the university wasn't named after him. The Woodruff name is all over campus: professorships, scholarships, buildings." After Woodruff's gift Nichols, who has written five books on fundraising, measured the number of $1 million and $5 million gifts in the same realm. "There was a geometric jump," he says.

Also while anonymity might get you to heaven faster and win friendly profiles, is isn't always as noble as it appears. Today's major philanthropists don't lift a finger without consulting a murderer's row of lawyers, bankers, and other consultants to calculate the less public-spirited ramifications of stashing money in a secret place, such as tax breaks and inaccessibility to an ex-spouse. "Generous people are generally quite smart," Nichols says. "They're careful. They do their homework." Still, he says, most donors don't care very much about the financial incentives of giving aggressively, but they are interested in knowing "how their gift can have the biggest impact possible." Naming (and shaming, when it comes to a donor's friends and competitors) doesn't just help; "it's something we in the development field desperately encourage them to do," Nichols says.

At some moment or another; it's difficult for any institution that relies on wealthy donors to avoid finding itself on the receiving end of its patrons' demands. (Recall that Sandy Weill raised eyebrows in 2002 when it was alleged that he helped an employee's children get into the 92nd Street Y's preschool, a coveted feeder to the city's private schools and another object of Weill largesse.) The rich, after all, are used to having their way. That's part of the appeal of philanthropy. "I want to give my money away rather than have somebody take it away," Weill once told the New York Times.

Naming rights—or, rather, renaming rights—have become a touchy

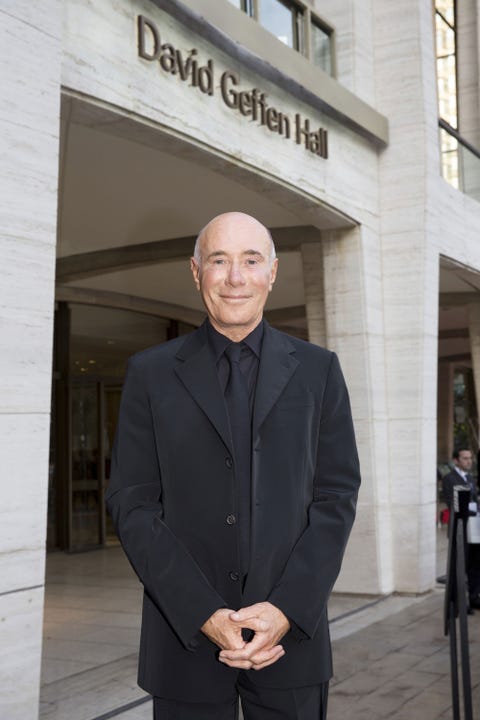

issue in these gilded times, because the size of some gifts to established institutions can rival the amounts that that were required to build them in the first place. (Paul Smith's College was initially endowed with a $2.5 million donation in 1937, which would be about $42 million today.) Nearly always the subtext is the brashness not merely of big money but of new money (what Apley called the "horsey and sporting set"). In 2008 the financier Stephen Schwarzman donated $100 million to the New York Public Library's main branch, which was then named after him. A to-do erupted over whether the carved letters spelling out his name at the entrance would be larger than or the same size as those of the original benefactor families, the Astors, Tildens, and Lenoxes. (They were indeed smaller.) And last year, when Lincoln Center secured a $100 million gift from David Geffen by offering to rename Avery Fisher Hall after him, an additional $15 million check was required to purchase the assent of the Fisher family.

The Geffen gift has ended up causing the biggest stir on the nonprofit circuit in years. After all, it's one think to etch new names into marble, and quite another to discreetly remove old ones. "It's just not the way we were," says Woody Brock, an economist and art collector who has donated to the Getty Museum and other institutions. "If you look at the Rockefellers or the Morgans, you would be shocked at how much they gave without most of it being named for them. The Metropolitan Museum of Art is really the Morgan Museum, you know. Paul Mellon built the National Gallery of Art, but he didn't request that it be named for him."

To look at the names of America's places of higher learning is to see your ruling class's ethnic composition during an altogether different era. Aside from Brandeis University, which was founded just after the Holocaust, how many colleges named for Jews come to mind? Or for Asians? Or African-Americans?

"How great would it be if someday there were colleges and universities whose names reflected a wild diversity of ethnicity of donor, that appeared to represent our population's best and most generous efforts?" says Charles Hamilton, the retired director of several prominent foundations. With regard to naming opportunities, Hamilton says, "You don't hear this discussed in philanthropic circles. You hear it couched in terms of the aggressive preoccupations of quote-unquote New Money."

At the same time it's not hard to see an undercurrent of anti- Semitism in all the wincing over the Weills, Schwarzmans, and Geffens—a sense that these newcomers, all of them Jewish, don't understand their place. In 2008, when Schwarzman made his gift to the library, Jamie Johnson, an heir to the august Johnson & Johnson family, wrote about just that in his blog for Vanity Fair: "Old-guard WASPs appear to feel threatened by the newly rich and their growing influence around the city, and dismiss new money as 'tasteless and gauche.' When discussing vastly rich people who are Jewish, it is not uncommon for them to use anti-Semitic slurs. 'Come on, though, it's not WASPs giving Jews a bad name, it's Jews giving Jews a bad name,' one said."

But if so much discomfort arises from Jews giving buildings Jewish names, plenty of people see the value of that struggle. "To the donors, putting their name on what are sometimes referred to as traditional WASP institutions—in culture, the arts, and education—is a sign that the Jewish community has arrived," says Robert Evans, a philanthropy consultant involved primarily with Jewish charities. "In fact, it's more difficult to get Jewish donors to give multimillion-dollar gifts to Jewish institutions than to causes that have no religious or ethnic affiliation. Ray Perelman, for example, recently made a $225 million gift to Penn, but his donations to Jewish charities have been much smaller. That probably has something to do with a desire to be recognized and accepted beyond one's own people."

"It's a shame that naming rights have become so important,"Hamilton says. "But ultimately it is the donors' money, and I do understand that, often, older patrons tend to be thinking about their legacy." Hamilton's own sensibility is revealed by the winking nature of the recognition his own family foundation requested in exchange for a gift to the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center at Alice Tully Hall. "There is a single girder named for our family, the main girder visible as you walk in on the left," he says. After a small private ceremony honoring the gift during the hall's renovation in 2008, the steel I-beam was coated in plaster. "But there's no plaque or public acknowledgment. Except for us, nobody knows it exists."

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

Different Games Name With Pictures

Source: https://www.townandcountrymag.com/society/money-and-power/a5341/naming-rights-philanthropy-anonymous-giving/

0 Response to "Different Games Name With Pictures"

Post a Comment